A Principal’s Mid-Year Reflection

It’s only three months into the 2016-2017 academic year, and we, the administrative staff at the Early College Alliance, are already gearing up for next year’s enrollment. The ECA operates in a “cohort” model, in which a large group of 10th and 11th graders begin the program together in the fall term of each year. A specific set of experiences both prior to and during the first ECA semester help new students from over 40 different prior educational settings to acclimate to this new and very different learning environment. Students get to know one another as they become integral parts of the ECA’s learning community. At the end of the first semester, a special celebratory luncheon is held to acknowledge the incredibly hard work that these incoming students have devoted to their learning, and to honor the milestone of completing that first, tough semester.

At this point, let me back up and recap some of the unique challenges that the ECA program—and this group of “First-Years” especially—have faced this semester. It’s a given in my mind that ECA students and their families are a little bit brave to leave their regular school and come to a university campus for high school. This experience is not really anywhere near the high school experience of most students. Not remotely. Unless the new family has other children who have gone through the program, ECA first-year students and parents/guardians have a lot of adjusting to do, from an increased homework load to the new physical campus environment to a very different school-family partnership.

A Difficult Semester

About three weeks into this fall, 2016 semester, I received an early-morning text from our Senior Administrative Assistant, Mrs. Jackson. It was a picture of a message spray-painted in red, white, and blue on our building, King Hall. At the top were the letters “K, K, K.” Below, the message, “LEAVE, N—ERS!”

Ugh.

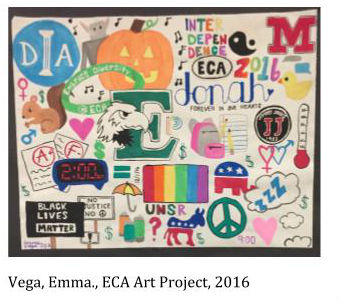

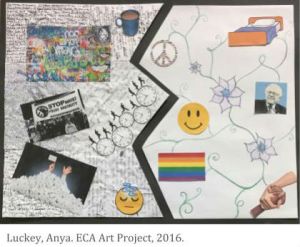

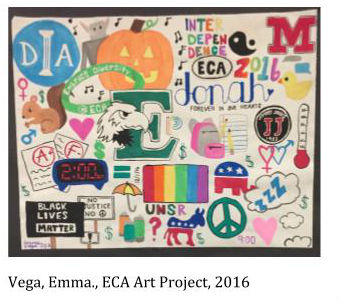

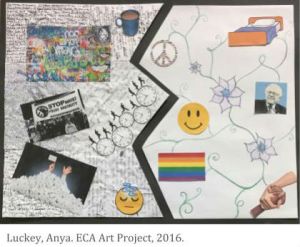

ECA student Anya Luckey perfectly captured the impact of the hateful message on the psyche of the program and its people: “Graffiti etched into our souls and the punch of racism bruised in our brains.” (Luckey, A., ECA Art Project, 2016).

As the police and EMU’s administration began their detective and rep air work, and college students and faculty mobilized to respond, ECA’s staff and students also felt the need to speak out. Ms. Burki spearheaded a Unity Chalking event, covering the sidewalks around our building with positive messages to counteract the hate that had been painted there. The next week, Mrs. Jackson and our Student Leaders pulled together an event to celebrate our diversity and commit to protecting that diversity, entitled “Unity in the Community.” (See photo, right). A new awareness of the impact of blatant and ugly racism right here in our midst was inescapable.

air work, and college students and faculty mobilized to respond, ECA’s staff and students also felt the need to speak out. Ms. Burki spearheaded a Unity Chalking event, covering the sidewalks around our building with positive messages to counteract the hate that had been painted there. The next week, Mrs. Jackson and our Student Leaders pulled together an event to celebrate our diversity and commit to protecting that diversity, entitled “Unity in the Community.” (See photo, right). A new awareness of the impact of blatant and ugly racism right here in our midst was inescapable.

Less than a month later, a smart, talented, and unforgettable ECA first-year student died by suicide at his home in Milan. For the first time in my nearly 20-year career, I was faced with the death of a current student—one who had already carved out a place of friendship and belonging for himself in our school with a physical, social, and intellectual presence that was huge. Teachers, themselves devastated by the news, read statements to inform students in ECA classes of Jonah’s death. Thus, supported by crisis responders from across the county, the grieving of our learning community began.

Still reeling from the loss of our student and attempting to regain our collective footing at a time of year that is incredibly intense in the best of times, a second racist graffiti incident took place on campus—just across the courtyard from King Hall. Protests and

teach-ins on our college campus gave rise to many classroom and office-hours conversations about racism, Black Lives Matter, social identity issues, politics in general and the 2016 Presidential election season in particular, and how to carve out and protect learning spaces that are physically and psychologically safe for all students. With these incidents fresh in their minds, our student representatives attended the 5th annual Washtenaw County Diversity Forum, and came away with the knowledge, skills, and passion to continue as leaders in diversity awareness and education at the ECA through our Diversiteam.

teach-ins on our college campus gave rise to many classroom and office-hours conversations about racism, Black Lives Matter, social identity issues, politics in general and the 2016 Presidential election season in particular, and how to carve out and protect learning spaces that are physically and psychologically safe for all students. With these incidents fresh in their minds, our student representatives attended the 5th annual Washtenaw County Diversity Forum, and came away with the knowledge, skills, and passion to continue as leaders in diversity awareness and education at the ECA through our Diversiteam.

Somehow, together we made it to the end of the fall semester—and to our Celebration on December 16. As the principal of this uniquely wonderful program, I was both excited and humbled as I walked the perimeter of the Ballroom, viewing the artwork that each ECA student contributed to the event as part of their final English classes. Students had been asked to design a visual representation of themselves (self-portrait) or of some aspect of the ECA program, focusing on capturing what this past semester has meant to them.

As this term has been an especially tough one, there was an explicit appreciation for the ways in which we have all been tested, individually and collectively. Many students expressed both visually and in words the impact that this intense term had on them—academically, emotionally, socially, and even physically. Common themes easily emerged as I took in images reflecting many of the values of this program: growth, hard work, interdependence (the theme for this school year), and diversity.

These themes were also reflected in the comments students made on the surveys they completed for their CLICK (Character, Learning, Involvement, & College Knowledge) class this semester. The “best things about the ECA” responses fell into categories where teachers who care/are good at teaching was the most common, and diversity & acceptance was next, followed closely by freedom, positive learning environment/good education, and, of course, free college!

Diversity: Critical Content for a Complex World

Given the complexity of the past semester at the ECA, in combination with my own professional values, I have been thinking a lot about the role of schools (and the ECA, in particular) in cultivating a school community that is both highly diverse and highly-functioning.

Diversity in school can be hard to talk about. There is a strong pull toward minimizing questions that attempt to explore the challenges of diversity:

- How might the experience of being a Black student on a campus where racist messages specifically targeted people of your race impact a student’s feeling of safety?

- How might a student’s immigration status, or that of their family members, influence the amount of mental energy they have to devote to learning?

- How might food insecurity impair a student’s ability to function with full attention on their school work?

- How might a health condition or disability (a student’s or family member’s) affect assignment completion?

- How might mental health/illness impact student learning?

- How might fear for one’s own (or one’s friends’) safety in a climate that feels intolerant and hateful detract from our students’ ability to focus on school?

- How might acts or threats of harassment, assault, and bullying—in or out of school—affect a school community?

The same minimizing instinct is true for questions about the benefits of diversity:

- How might the chance to listen to and learn from students of different races contribute to enhanced understandings of the ways in which history shapes our present?

- How much might immigrant students’ cultural heritage add to the awareness of our interconnected and global community?

- How might interactions between those from different income levels, or family structures, open students’ eyes to social realities that are often hard to see?

- How might students with differing genders and gender identities add critical, questioning voices to the conversation about what is possible for girls and boys (and others) in our culture?

- How might conversations between people of different religions expand the whole community’s awareness of the similarities that unite us?

- How can we possibly tap in to the riches of our multi-layered, multi-hued, multifaceted diversity to create an even more powerful and empowering learning opportunity for more and more learners?

It turns out that focus on diversity feeds an often-overlooked aspect of our students’ needs. Not always com fortable conversations, discussions about diversity are nonetheless central to helping students understand their own social identities, regardless of what

fortable conversations, discussions about diversity are nonetheless central to helping students understand their own social identities, regardless of what

those may be, in a complex and diverse world. Thinking expansively, creatively and critically about issues of diversity enable students to join in the civic discourse in a civil way—a necessity of high-level participation in both college and in life. More importantly, acknowledging the challenges and benefits of diversity helps our diverse students feel welcomed and safe, as well as heard and seen.

Social Justice: Equity & Access in Early Colleges

As an educator, my commitment to diversity is much more than an exercise in civic education. I am also a scholar of early colleges, which have deep roots as change-making, social-justice reforms in our nation’s educational landscape. Educational reform, at its best, is about deep and critical reflection about the best way to transform the practice of education. Transformation requires that we ask many questions about whether, and for whom education is working and not working, and what is required to make significant, high-leverage changes in the system. Early colleges ask these questions in the educational space that exists between high school and college.

The answer to our question is that inequality continues to plague our educational system—and those of us who work in the early college movement tend to believe that we can do something about it. Making high-leverage changes in the early college setting first requires an explicit acknowledgement of the unacceptable status quo that allows huge discrepancies in outcomes on the basis of race, gender, disability, income level, and other factors. This is the social justice foundation of our work.

Michigan’s public data-reporting portal, www.mischooldata.org, includes information about demographics and test scores for all of our schools in the state, and is adding post-secondary data year by year. Anyone can take a look to see how well high school programs prepare students for college success.

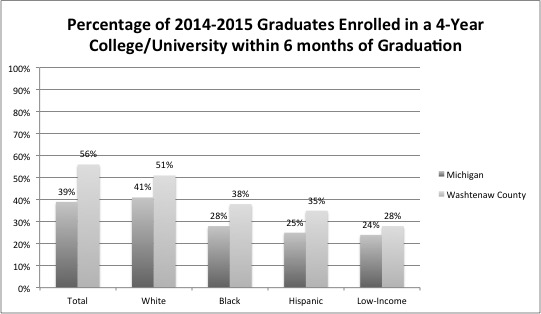

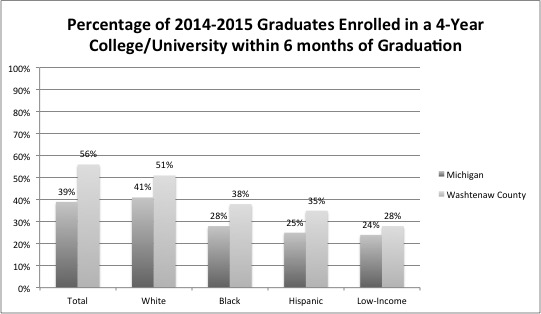

According to this site, only about 39% of Michigan’s 2015 graduates enrolled in a 4-year university within 6 months after they graduated. White students enrolled at a slightly higher level, 41%–but Black students did so at numbers 13% below their White counterparts. The numbers for Washtenaw County are not much better. Overall 56% of the graduates started at a 4-year university within 6 months. White students did so at 51%, Black students at 38%, Hispanics at 35%, and low income students in our county at only 28%. This information is only about enrolling in a 4-year college, and says nothing of actually completing a 4-year college degree. Figure 1, below, depicts these results.

Figure 1. Percentage of 2014-2015 graduates enrolled in a 4-Year college/university within 6 months of high school graduation, Michigan (statewide) and Washtenaw County figures (www.mischooldata.org).

ECA’s figures are much higher—with a reported 97% of our 2015 grads enrolling in a 4-year college after graduating, 90% of our Black students doing so, and 78% of White students. (It should be noted that the ECA’s numbers are very low, overall, and reports on http://www.mischooldata.org are incomplete as the state works on cleaning up the data for programs like ours).

The data on educational outcomes based on demographic subgroups are grim across several other key indicators that tend to predict college success: grade point average, ACT/SAT scores, dual enrollment credit earned in high school, and attainment of Bachelor’s degrees. It is a well-documented fact, nation-wide, that Bachelor’s degree completion over a 6-year period hovers around the 60%-mark (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2016). The lowest outcomes persist among students who are traditionally underrepresented in college: students of color, low-income students, and those who are the first in their families to pursue a Bachelor’s degree.

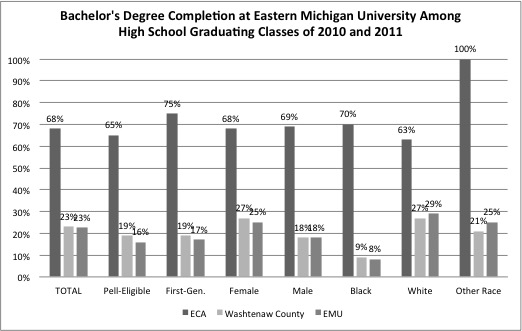

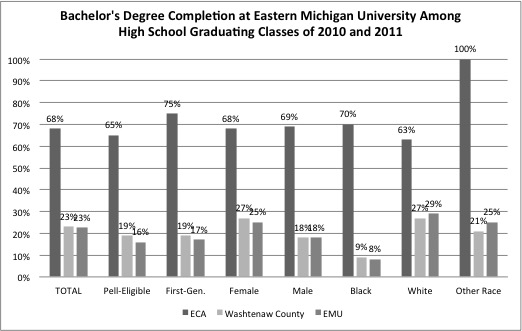

In my own 2016 study of graduates who continued their undergraduate education at Eastern Michigan University, I found that ECA’s student outcomes were significantly higher than that of their non-ECA peers at EMU (Fischer, 2016. Preview LINKED HERE). What is even more exciting, to me, is that the outcomes were statistically consistent across student subgroups. This consistency is quite different from the “all-EMU” and “Washtenaw County” populations, which showed markedly lower attainment rates for underrepresented populations (shown in the graph below).

Figure 2. Bachelor’s Degree attainment of EMU students who graduated from high school in 2010 and 2011, comparing the rate of all EMU students, all graduates from Washtenaw County, and only the ECA graduates in the sample, by demographic subgroup (Fischer, 2016).

Final Thoughts

Both anecdotes and the first data on Bachelor’s Degree attainment rates confirm that early colleges are perfectly positioned to make a positive difference in this story–for all students. The type of educational experience that the ECA and similar early colleges provides is perhaps especially critical for students who are traditionally underrepresented in college. The factors that research suggests are key to the success of our model, particularly among diverse student groups, reflect those things that our F2016 cohort spoke about in their projects and surveys:

- TRUE college prep skill-building courses that make sure kids are prepared for college

- Faculty mentors (CORE Advisors) who help students and families make the transition into college and help monitor performance in college

- Supportive peers and classmates who are focused on school success

- A diverse and welcoming group of students situated on a university campus—with access to the many resources that EMU provides; and, of course…

- Free college! The ECA provides a roughly $25,000 value in free tuition and books–the equivalent of a two-year college scholarship while still in high school.

There is a great deal of strength to build on as we recruit the next group of “First Years” at the ECA. As a critically reflective educator, I know that we have lots of continued work to do to cultivate a program that really lives the values of diversity and inclusion. But as we turn the corner into 2017, facing challenges and opportunities that will likely continue to test us and inspire us, I am confident about the strength of our learning community. I believe in our collective ability and willingness to be bold in tackling problems, to be honest about our areas for growth, and to be fearless in our support of each other as we do this work–students, staff, and families alike. This is the social justice foundation of my work.

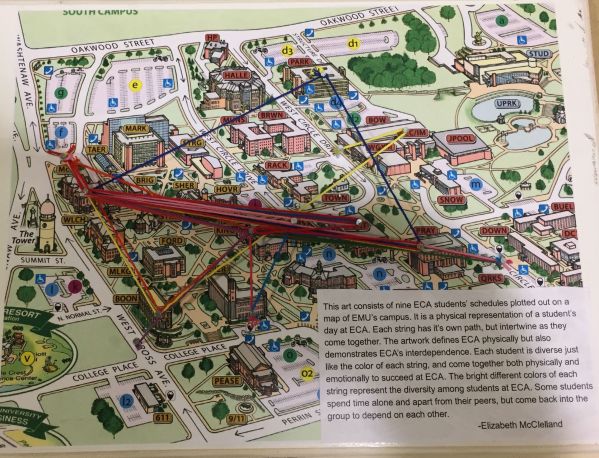

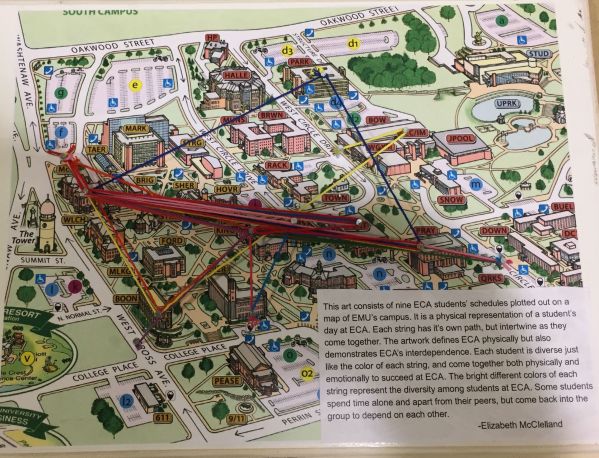

Figure 3. Image and description created by first-year ECA student Liz McClelland, capturing the essential pieces of our school culture.

few weeks, my thoughts–along with many of yours–have frequently turned to the issue of safety in our schools. With yet another horrific mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida two weeks ago, and then the killing of his parents by a student on the campus of Central Michigan University just last Friday, my heart is heavy. The safety of our young people–on and off school campuses–is so critically important, and should be the highest priority in all areas of our society.

few weeks, my thoughts–along with many of yours–have frequently turned to the issue of safety in our schools. With yet another horrific mass school shooting in Parkland, Florida two weeks ago, and then the killing of his parents by a student on the campus of Central Michigan University just last Friday, my heart is heavy. The safety of our young people–on and off school campuses–is so critically important, and should be the highest priority in all areas of our society.

planning Walk-Outs in many high schools (and middle schools) nationwide for Wednesday, March 14 at 10am. Some ECA students have approached me about this and will be sharing a student-led plan to take place on our campus for those who are interested in being part of this moment. It is not yet clear how widespread interest in this activity will be among ECA students in our high school classes; students who do not wish to take part in the walk-out will simply remain in the classroom. There will be staff supervision in the classrooms and alongside any walk-out, which is expected to last about 20 minutes. Lauren Slagter’s recent MLive article about the planned student-led activities provides some additional context about student protests.

planning Walk-Outs in many high schools (and middle schools) nationwide for Wednesday, March 14 at 10am. Some ECA students have approached me about this and will be sharing a student-led plan to take place on our campus for those who are interested in being part of this moment. It is not yet clear how widespread interest in this activity will be among ECA students in our high school classes; students who do not wish to take part in the walk-out will simply remain in the classroom. There will be staff supervision in the classrooms and alongside any walk-out, which is expected to last about 20 minutes. Lauren Slagter’s recent MLive article about the planned student-led activities provides some additional context about student protests.

from their old school or the ECA Academy 9th grade to our 10th/11th grade expectations. Furthermore, while the intensive and individualized attention on each student is a real strength of the program, it can also feel a bit intimidating to students. Many times, students (and parents, too!) harbor expectations that are unrealistic, sometimes putting pressure on themselves to be fully “credentialed” in their first semester in the program and immediately moving into college classes–and feeling stressed out and overwhelmed if their grades and credentials don’t match their initial hopes.

from their old school or the ECA Academy 9th grade to our 10th/11th grade expectations. Furthermore, while the intensive and individualized attention on each student is a real strength of the program, it can also feel a bit intimidating to students. Many times, students (and parents, too!) harbor expectations that are unrealistic, sometimes putting pressure on themselves to be fully “credentialed” in their first semester in the program and immediately moving into college classes–and feeling stressed out and overwhelmed if their grades and credentials don’t match their initial hopes.

geography, school experiences, religion, race, disability status, ethnicity, interests, gender, academic preparation, gender identity, income level, family type, home languages, national origin…and more!

geography, school experiences, religion, race, disability status, ethnicity, interests, gender, academic preparation, gender identity, income level, family type, home languages, national origin…and more!

membership(s)” (

membership(s)” (

air work, and college students and faculty mobilized to respond, ECA’s staff and students also felt the need to speak out. Ms. Burki spearheaded a Unity Chalking event, covering the sidewalks around our building with positive messages to counteract the hate that had been painted there. The next week, Mrs. Jackson and our Student Leaders pulled together an event to celebrate our diversity and commit to protecting that diversity, entitled “Unity in the Community.” (See photo, right). A new awareness of the impact of blatant and ugly racism right here in our midst was inescapable.

air work, and college students and faculty mobilized to respond, ECA’s staff and students also felt the need to speak out. Ms. Burki spearheaded a Unity Chalking event, covering the sidewalks around our building with positive messages to counteract the hate that had been painted there. The next week, Mrs. Jackson and our Student Leaders pulled together an event to celebrate our diversity and commit to protecting that diversity, entitled “Unity in the Community.” (See photo, right). A new awareness of the impact of blatant and ugly racism right here in our midst was inescapable. teach-ins on our college campus gave rise to many classroom and office-hours conversations about racism, Black Lives Matter, social identity issues, politics in general and the 2016 Presidential election season in particular, and how to carve out and protect learning spaces that are physically and psychologically safe for all students. With these incidents fresh in their minds, our student representatives attended the 5th annual Washtenaw County Diversity Forum, and came away with the knowledge, skills, and passion to continue as leaders in diversity awareness and education at the ECA through our Diversiteam.

teach-ins on our college campus gave rise to many classroom and office-hours conversations about racism, Black Lives Matter, social identity issues, politics in general and the 2016 Presidential election season in particular, and how to carve out and protect learning spaces that are physically and psychologically safe for all students. With these incidents fresh in their minds, our student representatives attended the 5th annual Washtenaw County Diversity Forum, and came away with the knowledge, skills, and passion to continue as leaders in diversity awareness and education at the ECA through our Diversiteam.

fortable conversations, discussions about diversity are nonetheless central to helping students understand their own social identities, regardless of what

fortable conversations, discussions about diversity are nonetheless central to helping students understand their own social identities, regardless of what

tart-of-the-year communications, I introduced a theme for the ECA community for the year: “We are in this together!–Cultivating the skill of interdependence.” The paradox of relying on others (which can feel like dependence) to be successful in one’s own life and work (which is key to independence) can be hard to learn! Interdependence deepens this dynamic with the explicit recognition that giving to the relationship is as important as taking from it–reciprocity is key.

tart-of-the-year communications, I introduced a theme for the ECA community for the year: “We are in this together!–Cultivating the skill of interdependence.” The paradox of relying on others (which can feel like dependence) to be successful in one’s own life and work (which is key to independence) can be hard to learn! Interdependence deepens this dynamic with the explicit recognition that giving to the relationship is as important as taking from it–reciprocity is key. David Gooblar (August, 2016) discusses how central class participation is to his class, not only to the overall “vibe” of the class, but also to the actual academic performance of the students. Citing a recent study on the topic, Gooblar explains, “…one student’s participation has a positive effect on another’s learning — student participation is a tide that lifts all boats” (See

David Gooblar (August, 2016) discusses how central class participation is to his class, not only to the overall “vibe” of the class, but also to the actual academic performance of the students. Citing a recent study on the topic, Gooblar explains, “…one student’s participation has a positive effect on another’s learning — student participation is a tide that lifts all boats” (See